Choosing the right driver for your speakers can be something of a minefield, particularly if its your first time. There are a number of things to be aware of, one of which is the power rating (specified in Watts)

Technological advances in materials are allowing Loudspeaker drivers to be developed with larger power handling, at the same time we have seen some loudspeakers drivers have their power ratings changed, with increases of 25% or more, but with apparently no change to the driver. Add to this the confusion of RMS Power, Continuous Power, Program Power, and Peak Power and it’s not suprising some of you are getting confused. This article aims to explain some of terms used, and dispel a few myths.

Q: My amp is rated at 400W per channel, will a 600W driver break my amp by drawing too much power?

A: NO. The power rating of your amplifier is a measure of how many watts it can deliver to the speakers before it reaches the limitations of its internal power supply and starts to clip/distort. The power rating of your speakers is the maximum power they can accept from an amplifier before they are in danger of overheating and burning out. Providing you have the corrent impedance load, your speakers are unable to draw more power than the amplifier is willing to give. https://speakerwizard.co.uk/impedance-faqs/

Q: If I replace my 400W speakers with 450W speakers will they go louder?

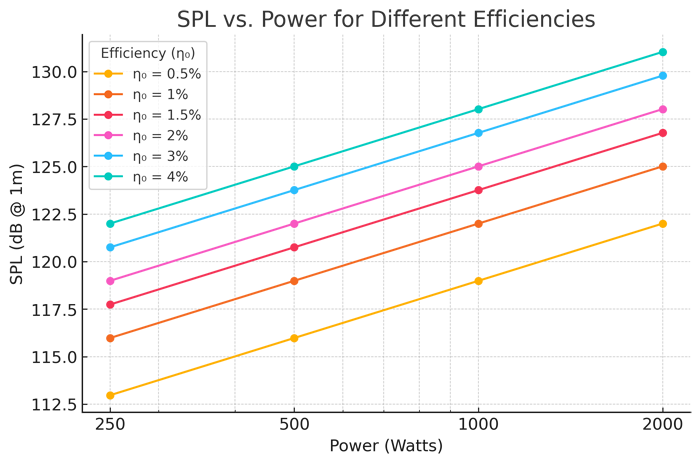

A: Not necessarily, the limiting factor is generally your amplifier, if you amp is rated at 400 Watts, you wont get any more than 400W output without severely distorting the sound, and potentially damaging your amplifier. If your amp can output 450W, then an increase in power handling may make your speakers go a little louder, but its possible they may be no louder, or in some cases quieter. The key factor here is efficiency, some speakers are more efficient than others. If you have two speakers operating at the same power level, and one is more efficient at converting electricity into sound, it doesnt take a rocket scientist to figure out which of the two will be louder. Most manufacturers give an indication of efficiency using the sensitivity figure measured in db@1W/1M (link to sensitivity)

Q: Which power rating should I look at?

If you’re reading this, chances are you are a novice, so for simplicity we suggest you use the continuous RMS power rating. Luckily, this is the one most manufacturers specify. You may also see Music Program Power Ratings, typically these are double the RMS power rating. If you see a peak power rating, its often meaningless, and serves little purpose. Peak power ratings are often four time the RMS rating, so if you see this anywhere, divide it by 4 to give you an idea of the real power rating.

Q: What do the power ratings mean?

RMS Power.

Sometimes referred to as Average Power, or Continuous Power. The term RMS here is incorrectly used, it is not RMS power in the true sense of the term, as Power does vary from positive to negative, it is the Voltage. The RMS Voltage is used in the power calculation, hence giving rise to the term ‘RMS Power’.

Over the years, various standards have been used in this ‘RMS Power’ calculation, including;

The IEC268-5 (1978) standard (IEC = International Electrotechnical Commission)

The EIA RS-426-A (1980) standard (EID = Electronic Industries Association)

The AES2-1984 standard (AES = Audio Engineering Society)

The AES2-2012 standard – which is becoming the most commonly adopted standard. Previously many manufacturers used the EIA standard, re-ratings some speakers using AES saw increases in power ratings of 25%, sometimes more. One example we are aware of was a high power 18″ driver, which was previously rated at 600W, and had the power rating changed to 800W overnight – with no changes whatsoever to the speaker design.

How is this possible? The AES power rating has a higher crest factor than the EIA rating, and is also for a shorter duration 2 hours for AES whereas the EIA rating was over an 8 hour test period. Some would argue this is not a totally realistic test. However for the layman, it is a useful benchmark for matching up driver power to speaker power. We’ll explain why:

Music Power:

Also know as Program Power, this is an indicator of the power rating of speaker use with ‘typical program materal’, which most of us call music. The RMS Power test is not done with music, it is generally done with bandwidth limited pink noise, which is a continuous signal. When was the last time you played music that sounded like static? Not often I bet. Music power takes into consideration that a bass beat is not continuous, it is a series of pulses. In between the pulses, there is no power being applied to the speaker, so when you average out the power over time, you can handle much more power.

What does this mean? Well you can exceed RMS Power for short periods of time, but not with a continuous signal. So if you play average music, you can usually run above RMS Power level quite happily in most instances, and with appropriate limiters in place, somewhere between RMS power and Music Power is generally a safe level. This is why I’m saying the Music Power is a useful benchmark – it helps determine amplifier power choice ‘roughly’ and is a good level to aim at to keep your drivers operating within safe parameters, if like most people, you try to push things just a little harder every now and then, you should still be fine, just as long as you don’t start treating music power as a long term continuous power rating, as you will almost certainly cause your speakers to fail if you do this.

Peak Power:

This is the maximum short term power that can be applied to the driver, and is typically calculated to be four time the RMS Power. I recommend you dont use Peak Power for anything except bragging to someone who doesnt know anything about sound.

Should I buy the most powerful speakers I can afford?

Probably not – It’s best to get speakers appropriate to your requirement. This is partly due to how speakers work. High power speakers are designed to have a high excursion (thats lots of cone movement) – in order to be able to handle the extra power, they typically have stiffer components, particularly with regard to the suspension. These high power speakers require a certain amount of power to overcome the mechanical resistances of the suspension. Comparing two extreme examples, of say a 100W speaker and a 1000W speaker running bass. The 100W speaker will have a low output for say, the first 5-10W put into it, once you are putting in 50W or so, the speaker will be at half its rated power, and will be (depending on sensitivity) fairly loud, ramp it up to 90-100W and the driver is giving all it can, potentially operating at its most efficient point. Lets suppose you only have a 100W amplifier, the 100W speaker will give you more output than the 1000W speaker. If you put your 1000W woofer on the end of your 100W amplifierm the first 40-50W of power will be used inefficiently, just to overcome the stiffness and resistance of the suspension, ramp it up to 100W, and you are still only tickling the 1000W woofer, you will find that you may need 200W running through the 1000W woofer to be as loud as the 100W woofer. As you keep ramping up the power, the 1000W woofer will ultimately create a lot more sound output than the 100W speaker ever will, but if you only have a small amplifier, you are better off with an appropriately matched driver.

So what if I exceed the power ratings?

You run the risk of overheating the voice coil of the speaker, and causing it to fail – but be careful – just keeping an driver within it’s recommended power rating is no guarantee of longevity. You also need to be away of excursion (often specified using Xmax and Xlim) as you can damage an driver through over-excursion without exceeding the power rating.

What about Power Compression?

Power compression is the little bugbear that can upset your best laid plans, and give you reason to throw the manufacturer’s specifications out the window. Many manufacturers choose to ignore power compression, some actively avoid specifying it or even mentioning it.

The sensitivity (efficiency) manufacturers specify is measured at a power level of 1W at a distance of 1m from the speaker. At 1W, very little heat is lost within the voice coil, so the driver is more effective at converting electricity into sound.

Its very common for loudspeaker voice coils to be wound from copper, which has a positive temperature co-efficient of +0.393% per degree C. It’s quite feasible for the voice coil of a high power speaker to reach 200 degrees Celsius, which could mean a change in the resistance of the wire to increase of 50% or more. Your 8 ohm driver will no longer be an 8 ohm driver, and the nominal impedance could rise to as high as 13 or 14 ohms. At full power, many drivers are no longer operating at their stated impedance, and they generating a lot of heat.

A good quality driver, with low power compression at its full rated power, could be 3-4 dB louder than a driver that suffers badly from power compression. Many modern designs are taking account of this, and making efforts to ensure driver cooling is maximised to counter the effects of power compression.