The Human Ear

Something often overlooked, but I believe to be an important part of designing, building and configuring loudspeakers systems is understanding some of the basics of the human ear, and the effects of sound on the human body. This article is intended as a brief introduction, and is by no means exhaustive.

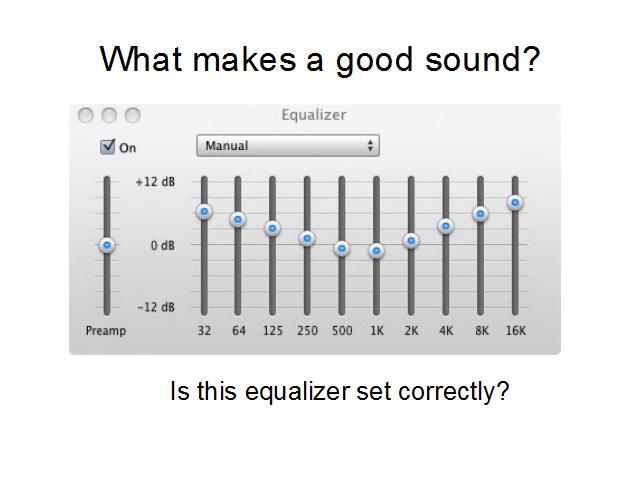

The smiley face equaliser

I’m sure you’ve seen this used, and possibly even done it yourself at some point in time.

Some would argue this is wrong, others that it is right.

The ‘smiley’ face curve often seen on graphic equalisers is similar to the effect achieved by the ‘loudness’ button on many hi-fi systems. It boosts the bass and treble to make it sound ‘better’ – but why do we think it sounds better?

Is it the speakers arent working properly? Maybe… we’ll discuss this later

But is something else wrong?

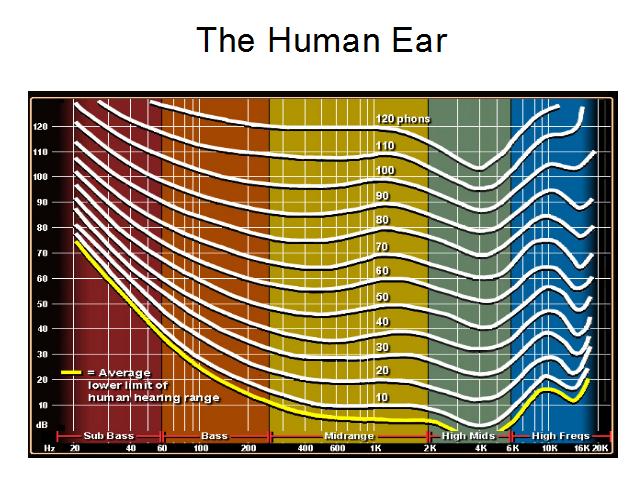

You might assume your ear works like a high quality studio microphone, with a flat frequency response across the audio spectrum, research has shown this is not the case. The way the ear responds to different frequencies varies considerably.

The graph above shows lines of perceived equal volume. First thing you will notice is that the smiley face equaliser curve is remarkably similar to the frequency response of the ear, but offset a little with the centre point around 3kHz and more emphasis on low frequencies. To some extent the smiley face can be explained as just naturally compensating for the human ear, making lower volume program material sound like we would expect it to sound at high volume.

Key Points:

Essentially deaf to bass frequencies: This goes some way to explaining the loudness functions on hi-fi systems, at low volume, we find bass very difficult to hear, and it needs boosting significantly. As the volume increases the curve flattens, requiring less bass boost. In effect the loudness function is giving our ears the same balance as ‘loud’ music, but at low volume. Many people are unable to hear detail in bass frequencies, and some actually prefer the sound of distortion in bass frequencies, as they feel the sound is ‘warmer’

Most sensitive to mid-range frequencies peaking at around 3-4 kHz: Approximately the same frequency as a human high pitched scream or yell, which is not dissimilar to a baby’s cry. This means our ears are most efficient at detecting important sounds, research suggests this is down to years of evolution. Many alarm designers utilise these frequencies to maximise effectiveness. With out ears being so sensitive in the mid frequencies, poor quality sound, particularly distortion will be extremely noticeable, perhaps this goes some way to explaining the smiley curve; a way of masking problems in the mid-band by overpowering with bass and treble? Many people find distortion in the upper-mid frequencies painful, and this is often linked with occurrences of tinnitus.

Response varies with volume: As the volume increases, our ears hear differently. This is one of the reason many high-end large scale PA Systems utilise Dynamic EQ, where the equalisers are programmed to change as the volume increases. If you do apply equalisation to your sound system, you may need to adjust it for low/high volume.

So is the smiley curve correct? In my opinion, most of the time it isnt, particularly if you are playing back pre-recorded music the original recording will have been tweaked by the engineer to sound ‘right’. What is definitely correct is to equalise your system to make it sound right at the volume it is being used, and the room it is being used in, and the type of program material being played through it. If this happens to be a smiley curve, so be it, but as a system operator you should resist the urge to just boost bass and treble in the hope it will sound better. If you find you are doing this a lot, you might want to consider upgrading your sound system.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.